12 Angry Men (1957) follows the deliberations of 12 jurors during a case involving an 18-year-old Puerto Rican boy accused of killing his father. Given the iron-clad evidence, witness testimonies, and troubled history, the defendant’s alibi seemed bogus. So with minds fixed on condemnation and hearts anxious to get back to their normal evening pleasures, 11 of the 12 jurors voted guilty during the preliminary vote. However, Juror 8 (played by Henry Fonda) wasn’t convinced the boy was guilty. Demonstrating the power of one person to elicit catalytic change, he questioned the uniqueness of the murder weapon, the veracity of the witness testimonies, and as life was too precious to be treated with such levity, he insisted they discuss and closely inspect the evidence before dooming the boy to the gallows.

Since the votes must be unanimous, the other 11 jurors were tasked with explaining why they felt the boy was guilty. As they deliberated, the evidence seemed less concrete, the witness testimonies less valid, leading to a gradual but sure osmosis of jurors from the guilty to the not guilty side of things. During their discussions, we get to know the jurors better; their biases become obvious as well as their penchant for filtering things through the lens of their personal experiences.

Aside from the thought-provoking plot, authentic acting nail-biting suspense, and the fact that the jurors are never addressed as anything other than their numbers, 12 Angry Men (1957) is a confirmation that cinema, good cinema, died after the 20th century.

At the jurors’ table, a lot of valid issues are subtly analyzed; issues that are still realities for many people today. One of such realities is implicit bias.

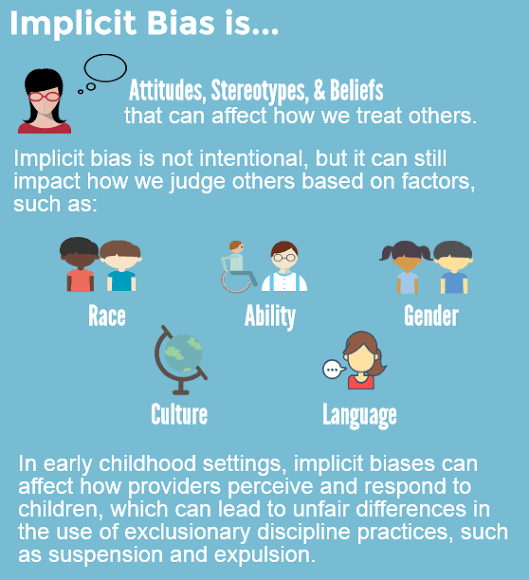

Implicit biases (also known as implicit social cognition bias) are those unconscious ideas or beliefs we hold against others which are triggered by the rapid and automatic mental associations we make between people, ideas, and objects, and the attitudes and stereotypes we hold about those people, ideas and objects. It is deep-seated in the brain, below the conscious level, and can run counter to people’s expressed beliefs; you can be explicitly unbiased but implicitly biased.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, as implicit bias results from a series of decision-making shortcuts that have kept our species alive. These instantaneous decisions can sometimes be right and trigger fight-flight responses that helped us survive during primordial times. The unfortunate thing, however, is that when we are blinded by bias, we miss out on reality.

Juror 3 (played by Lee J. Cobb) is a lesson in biases and a social psychologist’s wet dream. He has a mercurial temper and is the most passionate advocate of the guilty verdict. At first, his bias was implicit when he says the boy was a dangerous killer and that was clear for all to see. It didn’t matter that he was just 18. In his opinion, that was old enough. However, with each defection of the jurors, his bias grows into a tempest of implicit bias.

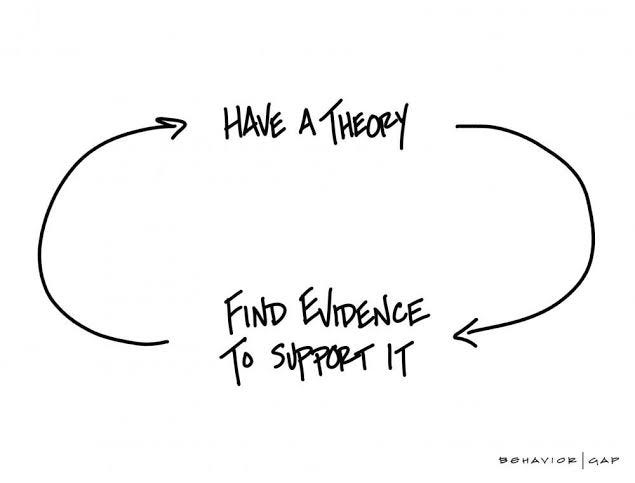

Confirmation bias is the brain’s tendency to confirm first impressions/hunches. In 12 Angry Men (1957) we observe this when Juror 3 refuses to believe, even when presented with convincing evidence, that the young boy probably didn’t kill his father. The boy had a history of crime, lived in a rundown neighborhood, and had clashes with his father. The way this juror saw it, the boy was a hardened criminal; besides, violence and teenagers were like peanut butter and jelly.

Juror 3 held on convulsively to these tidbits of information that confirmed his verdict and refused to consider the remote possibility that the boy might be innocent.

In an inversion of the presumption of innocence, the defendant was, in the eyes of most of the jurors, guilty until proven innocent by being from a broken home and a filthy neighborhood. Juror 3 makes this obvious when he says, “we tryna put a guilty man in the chair where he belongs.” As humans, it is natural that we sometimes filter decisions through the lenses of our personal experiences. Juror 3’s strained relationship with his son and his subsequent disaffection with youth blinded him from seeing the condemned teen in a favorable light. When talking about his frayed relationship with his son, he exhibits self-serving bias by never owning up to the role he played in his son’s estrangement.

Juror 10 (played by Ed Begley) is not left out as he makes vitriolic comments about ethnicity and the hoi-polloi’s supposed predisposition to crime. According to him, he had lived among “them” all his life and knew for sure they were born liars. Juror 9 refutes this ignorant line of thought by telling him no one has a monopoly on the truth. Juror 4 (played by E.G. Marshall), a rational and unflappable stockbroker, notes the defendant was born in the slums which were, in his opinion, breeding grounds for criminals.

This discomfits juror 5 (played by Jack Klugman) who grew up in similar environmental circumstances as the defendant. Juror 10 supports Juror 4’s point of view and proclaims that kids that crawl out of slums are real trash. He goes further to say the boy is a common ignorant slob who “don’t even speak good English” and people like him are genetically mendacious, unfeeling, and violent, much to the distaste of his fellow jurors.

Every one of us has a seat on that jury, but what differs is the degree of our bias. Some of us like jurors 3 and 10 are implicitly and explicitly biased and unwilling to let go of that bias. We see a certain demographic of people as less than and as bias, whether implicit or explicit, is driven by the Us-versus-them mentality (or what is known as the ingroup-outgroup phenomenon), we absolve ourselves of those flaws.

We assume overweight people and the elderly are sluggish and incompetent, minorities are ignorant and violent, and write off ugly people as mean. Some of us, like juror 4, hold our biases tightly but in the face of rationality, are willing to let them go. Some of us, like the rest of the jurors (excluding juror 8), are what I like to call tide riders, implicitly biased, never going against the grain but being amenable to change, nevertheless.

The final group of people, like juror 8, understand that appearances can deceive and, with human nature, nothing is ever really set in stone. Once the cause is just, they are willing to go against the grain and be that lone, still voice of reason amidst the drone of irrationality. Implicit bias is malware we can never be rid off. However, if Fonda’s character in 12 Angry Men (1957) is anything to go by, we can learn to consciously rewire ourselves to override it when it tries to overpower rational thought.

Originally published on Medium.

Like what you read? Check out Ihairesponsibility and African Hair and The Myth of the Good Person.

FyefqmVguCAl