One of the many things I love about travel is how it makes it so easy for one to become an observer and a beneficiary of life’s many wonders. Like a friend of mine would often say, travel teaches you to become a tourist in your homeland. As we drive through shrugging hills cloaked in swatches of lush green and drab gray, I think of how different Abuja is from the Southeastern part of the country where I live. Observing how the opulence of Asokoro as a whole intersperses slyly with the squalor of next door Asokoro market, I realize how Abuja is a compendium of most of life’s most precious paradoxes.

On all my trips to Abuja, I soak up experiences that are deeper than beautiful vistas and houses squatting on either side of the winding road. I observe and experience people too. In that respect, Abuja is no different from any other state in Nigeria- or anywhere in the world. This particular trip was a confirmation of what I believe is the African problem.

Different people have different theories on why Africa (read Nigeria) is the way it is.

Some believe the government is at fault.

Others say it is the ever interfering hands of foreign bodies.

Another demographic believes intransitive factors like tribalism, sectionalism, godfatherism, and other -isms are at fault.

And they are not wrong.

Yes, politicians ferret money away abroad and run the nation into the dust.

Yes, pale, invisible hands sometimes guide the movements of the country.

However, all these are superficial answers to a skin-deep issue.

Anyone that has ever been to any embassy in Nigeria, for an exam or a visa appointment, knows how much of a learning experience can be. You become Po. Only this time, the gift you are mastering is patience and Master Shifu is the gateman at the entrance, testing all your limits.

Yes, the gateman.

Like a friend of mine that had an appointment at the US Embassy would say, “It is not the Americans inside that are the problem. Those ones are nice to a fault. The problem is the Nigerians at the gate.” With forbidding expressions and an air of importance thicker than an IG model’s body, they go about their jobs zealously, yelling and bodily pushing people if the need arises.

And I get it.

Nigerians can be unruly. Add visas and a pinch of desperation and the unruliness skyrockets. The only thing unruly and desperate Nigerians respond to is force- and as they say, the end justifies the means, right?

The African man’s problem is the man in the mirror. Things took a twist when an Italian came to the embassy. He had no mask on, ignored the queue of people there, and was as rude as sin to the gatemen. Their response? “Chief, wear your mask abeg. Corona dey!” They smiled solicitously as he stomped into the premises. The smile turned longanimous as he audibly cursed at them in Pidgin while tugging on his mask. When he left, the gatemen went back to playing the role of Pharoah.

Another case involved a Chinese expatriate, his Nigerian security outfit, and customers at a popular Nigerian commercial bank. The Chinese national was able to jump a very long line of disgruntled customers in front of the bank, thanks to his security team muscling him through. When they got to the front of the line and were waiting for the doors to open, a certain customer voiced his discontent at what just happened. Guess what happened? These mopol guys beat him.

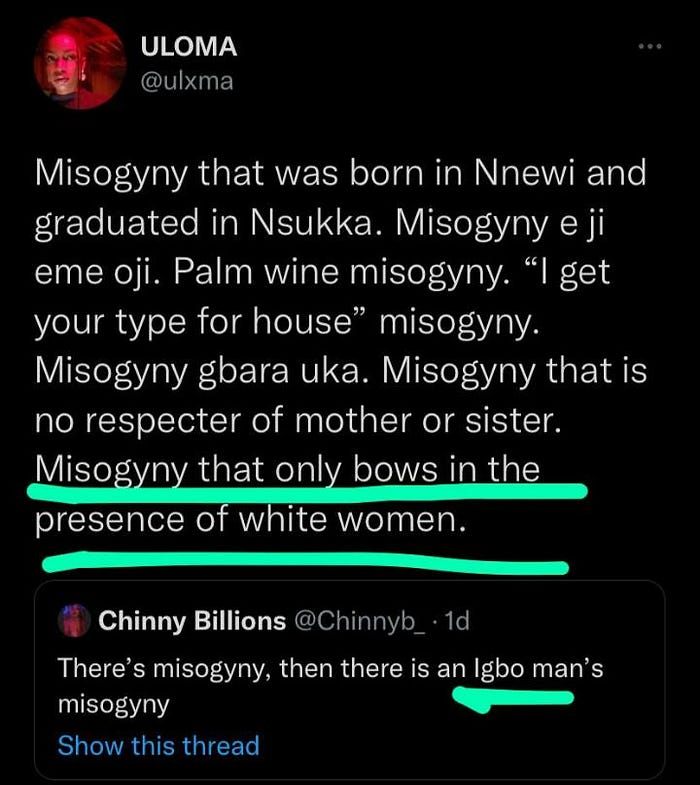

This might seem trivial and even unnecessary against the backdrop of issues we have in Nigeria. However, trivialities like these are oxpecker birds, pecking on deeper issues that are not as black and white as they seem. The difference in treatment of two different groups that came for the same thing was interesting to observe. While one group was more or less coddled and let off with a “tut-tut”, the other group was herded like sheep and sometimes verbally abused. In the second case, the man was beaten for being bold enough to point out nonsense behavior.

In life, people only treat three classes of people with respect and consideration:

- People they care about

- People they respect/fear

- People they perceive to be better than them

Excellent treatment is often not guaranteed in the first scenario especially when you consider how loved ones are familiar to us and the close relationship familiarity has with contempt. However, it is almost always guaranteed in the second and third scenarios. When we fear/ respect people or perceive them to be better than us, we treat them better. In my language, this perception that one is better than another is called “Nkali”. Nkali was at play when those gatemen condoned the Italian’s verbal diarrhea and let him jump the queue to boot. When one person is perceived as superior, another person within that context is perceived as inferior. The superior person (and all that pertains to him) is treated with respect. As for the inferior person, if you do anyhow, you see anyhow.

This explains why over here we treat each other like dirt. Add an expatriate to the mix and the story changes.

Or why (some) African men become the poster child for “husband of the year” when they marry foreigners.

Or why most Nigerians comport themselves, follow basic traffic rules, and separate recyclables from biodegradables when they leave the country; things they generally took for granted here. And when you point this out, they reply, “Omo, Jand no be Nigeria. You gats behave yourself.” (Abroad is not Nigeria. You have to behave yourself)

On our becoming journey, there is a need for intensive shadow work. We need to work on the man in the mirror and confront some uncomfortable truths that are fast becoming the African narrative. We need to confront some complexes we have that make us see everything African as inferior, local, and fetish and everything foreign as superior, standard, and good.

It is easy to absolve one’s self of blame when reflecting on personal issues. It takes a certain amount of introspection, psychological maturity, and emotional intelligence to realize the role you must have played in the situation.

I remember stories my Dad used to tell us about slavery and the olden days. Of how people sold their stubborn and ne’er-do-well children to the slave masters (because they believed they would not amount to anything). Of how people sold their children just because they stared too long at their parents as they ate eggs or meat (back then, only adults ate meat and eggs). They would say, “Anya di ya n’anu nnukwu, o ma ba ulu,” (He is too fixated on meat. He won’t amount to anything). They usually sold the child afterwards. My Dad will always end by shaking his head sadly and saying, “Ndi gboo melu alu” (Our ancestors committed atrocities). Sadly, the stories don’t end there. Stories abound of people selling their kinsmen for mirrors and other shiny thingamabobs or to get money for ozo titles.

We blame the white man for slavery, conveniently forgetting people that looked just like us enabled slavery. Like the Igbo saying goes, O bu oke no n’uno gwalu oke no n’ezi na azu di na ngiga (it is the house mouse that told the field mouse that there is fish in the basket). It is not the white man that calls you a dot in a circle or dismisses your tribe as dirty. It is people who look like you and me. I have a theory that, at the root of it all, many Africans dislike being African. They dislike the man in the mirror and thus reject everything being African stands for. It’s basically projection 101 at work.

While I will not deny the roles external factors play, externalizing all our problems and denying the culpability of our individual and collective actions will take us nowhere. It feeds the victim narrative, justifies your actions and inactions, and prevents icky feelings like shame and contrition, but it doesn’t encourage meaningful growth. And to be honest, none of us really has so much control over the externalities of life.

To get to the heart of the African problem, we have to clean the fog and take an intense and comprehensive look at the man in the mirror.

Originally published in Medium.

Like what you read? Check out Akajiuwa: A Tale of Three Artists and When the Lights Dim: Review of Gaslight (1944)

Comments 2